Low sodium diet: the benefits of reducing salt and what foods to eat

A low sodium diet could be life-saving for people with conditions like high blood pressure.

The low sodium diet is recommended for people with heart disease, high blood pressure and kidney disease. While sodium is a mineral that can be found naturally in many everyday foods, it is also a main element of salt, which is made of sodium and chloride. Although some of the sodium in our daily diet comes from our natural food sources and table salt, the main source of hidden salts are processed products, takeaway food and meals in cafes and restaurants.

If you are someone who has high blood pressure, kidney disease or is at risk of heart disease, adapting to a low sodium diet can have drastic results on your health. Studies have shown that a low sodium diet has been proven to lower blood pressure. Registered nutritionist Katharine Jenner says: “The biggest benefit is keeping your blood pressure from rising to dangerously high levels, which can lead to strokes and heart attacks. However small everyday benefits you might see are less bloating, fewer headaches and being less dehydrated.”

What is the low sodium diet?

A low sodium diet limits the amount of sodium, or salt, you eat. While some sodium is important for the body - it helps to maintain the balance of water and minerals - too much of it can lead to issues like increased blood pressure. This in turn increases your risk of heart disease or a stroke.

According to the World Health Organisation, most people consume on average 9 to 12g of salt per day. This is around twice the recommended daily allowance, as the NHS> recommends it should be no more than 6g, around one teaspoon.

While some of the sodium in our diet comes from natural food sources or the table salt we use, the majority of it comes from pre-packaged or processed foods. It's also usually high in the meals we order in cafes and restaurants. This is because it is used for flavourings, as a binding agent and as a preservative.

So if you’re looking to follow a low sodium diet, the best way to do so is to reduce your intake of processed food as much as possible.

GoodtoKnow Newsletter

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

Katharine Jenner, who is the director of Action on Salt, says: "A low sodium, or salt, diet is an approach to lower blood pressure, bloating and headaches, and involves avoiding foods with high salt. These include packaged foods where salt is added, like sauces, ready meals and crisps and where salt is used in the manufacturing process like bacon, sausages and cheese.”

One of the main problems is that some food labels list salt and others sodium, meaning you have to keep an eye out for both. Bear in mind, however, that salt is equal to two and a half times the same amount of sodium. So if a label only has sodium listed, work out the amount of salt by multiplying it by two and a half. For example, 1.2g sodium is equal to 3g salt.

What’s the difference between low salt and low sodium?

The terms 'low salt' and 'low sodium' are often used interchangeably. This is because salt is made of the minerals sodium and chloride. So anyone following a low salt or low sodium diet will be following the same plan.

Registered dietician Katharine Jenner explains: "Salt is made of sodium and chloride. So theoretically, ‘low salt’ is just 'low sodium chloride’. The term 'low sodium’ can actually be used for anything low in sodium, so sodium bicarb or sodium nitrate for example. However, in reality in the UK, food manufacturers extrapolate ‘salt’ from ‘sodium’. So, they are the same - except in the case of ‘low sodium table salt’, which has much of the sodium replaced with potassium chloride. So ‘low sodium’ is a much more logical name."

Also bear in mind - that sodium is what’s found in our food, especially in processed foods, while salt is what we add to our food. There are also different types of salt…

- Table salt – stripped of its minerals to give it that fine texture. Additives may also be added to prevent clumping.

- Sea salt – harvested from evaporated seawater. Sea salt contains minerals such as zinc, potassium, and iron, giving it a more complex taste.

- Rock salt – chunkier in size compared to table salt. Often used to preserve meat.

What are the benefits of a low sodium diet?

1. Lowers blood pressure

Research by the Royal College of Physicians has shown that high blood pressure is the biggest risk factor for global disease because it can lead to heart disease and strokes.The good news is, that following a low salt diet can have pretty fast results in reducing your blood pressure. >This 2019 study found even a modest reduction in salt intake over a prolonged period led to a fall in blood pressure.

2. Slows kidney disease

One of the roles of the kidneys is to remove excess sodium from your body. So people with kidney disease have to be particularly careful about the amount of salt they eat. Although researchers agree that more work is needed in this area, this JASN study found that restricting sodium should be encouraged in patients with chronic kidney disease in order to reduce its progression.

3. Reduces bloating

Diets that are high in salt can also lead to bloating. This is because it encourages your body to hold onto fluids you eat and drink. In a 2019 medical trial 412 participants were put on a high-fibre, DASH or low-fibre or Western diet. On their assigned diet, participants then ate three sodium levels, low, medium or high, in 30-day periods, with 5-day breaks between each period. Researchers found that regardless of the diet, a high sodium intake increased the risk of bloating.

4. Fewer headaches

Patients with high blood pressure may also find that they suffer from headaches. Although medics aren't sure of the exact cause, research suggests it's likely to be because higher salt levels cause the blood vessels in the head to expand.

Research has found that by lowering blood pressure, patients may experience fewer headaches as an added bonus. A 2016 study by Johns Hopkins University of 975 men and women aged 60-80 for example, found that a reduced sodium intake (although recommended for blood pressure control) had the added benefit of reducing headaches.

5. Reduces dehydration

Studies have shown that having a higher intake of salt can lead to dehydration. In this study which looked at young adults’ drinking habits, researchers found that although participants with a higher salt intake drank more than those with a lower salt intake, they still had lower hydration levels. It recommended reducing the consumption of salt among young adults.

Low sodium foods

- Fruits – Apples, bananas, oranges, pears, peaches, plums, strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, grapes, figs, pomegranates, passion fruit, kiwis, avocados

- Vegetables – Potatoes, carrots, broccoli, cauliflower, peppers, aubergines, courgettes, tomatoes, spinach, garlic, sweet potatoes, peas, sweetcorn, beans

- Meat - Beef, pork, lamb, chicken, turkey, duck

- Fish - Salmon, tuna, cod, haddock, plaice, seabass, white fish

- Shellfish – Prawns, crab, lobster, mussels, oysters, scallops

- Wholegrains – Wholegrain bread, brown rice, couscous, buckwheat, quinoa, bulgar wheat, whole oats

- Legumes (with no added salt) – Beans, lentils, chickpeas

- Dairy - Milk, low salt cheese, yoghurt, unsalted margarine/butter, cream, ice cream

- Eggs

- Nuts (unsalted) - Cashews, hazelnuts, Brazil nuts, walnuts, pistachios, etc

- Seeds – Pumpkin, chia, sunflower, poppy, sesame, etc

Try to buy fresh, unprocessed food where possible. When buying tinned food look for products that have no added salt.

High sodium foods to avoid

- Fast food and takeaways - Burger, fries, pizzas, fried chicken, curries

- Snacks - Crisps, tortillas, salted and dry-roasted nuts, crackers, olives, pickles

- Pre-packaged meals - Pizzas, pasta

- Processed meat - Bacon, sausages, ham, salami, chorizo

- Salty fish - Anchovies, smoked fish, salt fish, prawns

- Canned food - Vegetables, beans, pulses, soup

- Sauces - Pasta sauces, salad dressings, ketchup, mayonnaise, soy sauce, yeast extract

- Gravy and stock cubes

When thinking about high sodium foods to avoid, the best place to start is with processed and pre-packaged food. This is where the majority of salt in our diet comes from. Also, it is worth being aware of 'hidden' salt in canned goods and sauces.

How to lower your sodium intake

While it may feel daunting at first to have to reduce the salt in your salt diet, there are plenty of easy tips for lowering your sodium intake. These range from checking the packaging of the food you buy in the supermarket, to thinking carefully about the choices you make when ordering dinner in a restaurant. Cooking from scratch and finding different ways to season food can also help.

Katharine says: “About 75 per cent of the salt that we eat comes in the packaged foods that we buy, and in the meals we order out of the home in cafes and restaurants or via deliveries. So rather than just stopping adding salt to your food when cooking, you really have to look at choosing less salty options from those on the menu and on the shelves.”

1. Read food labels

It sounds obvious, but always check the nutrition labels on the packaging of the food. In the UK there is a helpful traffic light system, where foods which are high in salt will be red and low in salt will be green. Compare labels for products you buy regularly and try to make healthier swaps where possible.

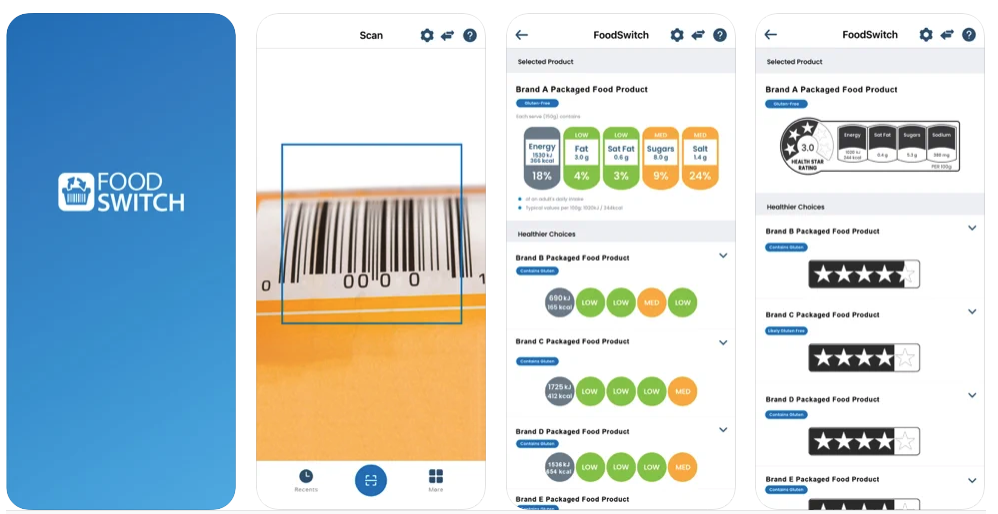

2. Download the FoodSwitch app

Action on Salt has a free app called FoodSwitch UK – which tells you how much salt is in your packaged food and offers you less salty alternatives.

3. Don’t automatically add salt

The NHS recommends tasting your food first, whether you’re cooking yourself or eating out. Often people add salt out of habit when it is not actually needed.

4. Find different ways to season your food

There are plenty of other tasty ways to season your food, rather than using salt. Use black pepper on fish, fresh herbs in pasta and ginger and chilli in stir frys.

5. Avoid added salt in tinned food

When you are buying tinned food, such as beans or vegetables, opt for those without added salt. Once you’ve added them to the meal you are preparing you won’t notice the difference.

6. Cut back on the fast food

While we all love the odd fast food treat, there’s no denying that they are usually packed with salt. Try to reduce the amount you eat and if you do order one look for healthy alternatives, such as a salad rather than fries.

7. Eat less processed meat

Processed meat is often high in salt, as it is used for flavouring and preserving. Try to cut back on the number of sausages, burgers, salami and chorizo you eat. If you do buy bacon, opt for reduced-salt unsmoked back bacon.

8. Check the menu for healthier options

Food in restaurants and takeaways often have high levels of salt. Think carefully about the toppings, sauces and sides you order, which can all add up. For example, on a pizza opt for vegetable or chicken toppings, rather than pepperoni or bacon and for a Chinese or Indian meal choose plain rice which has less salt than pilau or egg fried rice.

9. Go easy on the sauce

Lots of sauces and salad dressings have high salt content so check the labels on products like mayonnaise, ketchup, mustard and soy sauce. Try making your own salad dressings at home or ask for them to be served on the side of your meal at a restaurant.

10. Adapt the English breakfast

Try to make the traditional English breakfast healthier by opting for poached egg or mushrooms on toast. If you do have meat, choose bacon or sausage, rather than both.

11. Choose healthy snacks

Crisps and salted nuts are so easy to snack on, but also quickly ramp up your daily salt intake. Try replacing them with unsalted nuts or crackers or chopped up vegetables like carrots and peppers.

How long does it take to reduce sodium levels?

It doesn’t actually take very long to reduce sodium levels and people who follow a low sodium diet often see a reduction in their blood pressure within a matter of weeks. The amount by which it lowers will be dependent on a number of factors, including how much salt you previously consumed in your diet and how much you have reduced your salt intake by.

This review of 33 studies lasting five weeks or longer found that in people aged 50-59, who had a reduction in daily sodium intake of around 3g of salt would, after a few weeks, lower systolic blood pressure (the pressure in your arteries when your heart beats) by an average of 5 millimetres of mercury (mmHg)> and by 7 mmHg in those with high blood pressure. Diastolic blood pressure (which measures the pressure in your arteries when your heart rests between beats) was lowered by about half as much. The review also estimated that a reduction in salt intake by a whole Western population of this kind would reduce the incidence of stroke by 22% and of ischaemic heart disease by 16 per cent.

Registered dietician Katharine Jenner says: “You can do this instantly, and you can see the effects very quickly. Blood pressure can be reduced within weeks. Your taste buds take a bit of time to adjust to less salt if you do it too quickly, but they will – so give them time. Much as if you slowly reduce the amount of sugar added to your tea, after a couple of weeks you won’t enjoy tea with sugar in it anymore.”

Low sodium diet: a nutritionist’s verdict

Katharine told us: “If you have raised or high blood pressure, a low sodium diet could literally be a lifesaver. Low sodium diets might seem a bit specific to others, but moving away from high salt diets means you are more likely to have less processed and takeaway foods. This means your diet is likely to be richer in more nutritious ingredients and that can only be a good thing. As with all diets, it is small and lasting changes that you can stick to that make a difference. So give it a go and see if you can make it stick. I used to have a high salt diet, without realising it, and now I can finally appreciate what real food is meant to taste like – and it’s delicious!”

Video of the Week:

Emily-Ann Elliott is an experienced online and print journalist, with a focus on health, travel, and parenting. After beginning her career as a health journalist at The Basingstoke Gazette, she worked at a number of regional newspapers before moving to BBC News online. She later worked as a journalist for Comic Relief, covering stories about health and international development, as well as The Independent, The i, The Guardian, and The Telegraph. Following the birth of her son with neonatal meningitis, Emily-Ann has a particular interest in neonatal health and parental support. Emily-Ann has a degree in English literature from the University of Newcastle and has NCTJ and NCE qualifications in newspaper journalism.