How to talk to your kid about feelings and 7 therapist-approved ways to connect

We share examples of conversations to try with your kids that might help

Joanne Lewsley

Is your child struggling to open up about their emotions? You're not alone. As children grow, they experience a wide range of emotions but may find it difficult to express them.

Creating a safe space for these conversations is crucial, whether you're discussing everyday experiences or wondering how to talk to kids about divorce or how to talk to your kids about cancer. Some parents find that using toys to support their child's mental health is useful when tackling difficult conversations.

What our writer learned

I'm a big expressor of emotions in our house so I'm glad that's a GOOD thing, but I'm guilty of trying to make everyone else the same as me. I've learned that I need to make more space and silence for others to process their emotions but remember to reassure them that I'll be there when they're ready to talk.

We speak to a range of experts who offer effective strategies to help your child open up and continue the conversation. Psychotherapist Kemi Omijeh emphasises the importance of parents being in the right mindset and advises, "Having those difficult conversations about feelings starts with ensuring that you are okay and ready to engage with your child."

In this article, you'll find expert-approved methods for encouraging emotional discussions, real-life examples, and guidance on what to do if your child remains reluctant to talk. Remember, fostering emotional intelligence requires patience and the right approach.

How to talk to your kid about feelings

Firstly, model it. Use simple language to describe your own emotions every day, encouraging them to do the same. Create a safe space for them to express their feelings through play, books, or creative activities. Listen attentively when they share, validate their feelings, and be patient as you both learn to communicate emotions more effectively.

It's easy to communicate with others in a way that means we don't truly listen. How often do you ask someone how they are and not really take in the response? You'll probably find it's the same the other way around - another parent shouts to you on the school run, "How are you," and you'll automatically say that you're absolutely fine, even if you're about to burst into tears in an exhausted heap on the floor.

It's important to have a deeper connection with our children when we explore their feelings. We know this can be difficult, especially if a child struggles to understand what they're feeling, let alone talk about it. Older children and teens can be even more closed off—they might understand their feelings better but choose not to talk about them for many reasons.

GoodtoKnow Newsletter

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

Kemi Omijeh tells us, "It can be really hard to engage in feelings talk if this wasn’t role-modelled for you and you weren’t raised to talk about feelings. I would encourage you to lean into that discomfort as it can be healing and empowering for you and help you break the cycle. A safe and creative way to explore feelings if you are not used to it is play, books, and masks. You can play with your children’s toys and characters and have them express a range of feelings. You can even create feelings/emoji masks using paper plates."

Heidi Soholt is a highly experienced BACP-accredited psychotherapist who specialises in helping children and adults overcome a wide range of issues. Heidi told us, "Expressing feelings can be challenging, but teaching children to do so will provide an important outlet for emotions. Using simple terms such as sad, happy, and worried to describe your own feelings will teach children the language needed to articulate emotions and signal that it is okay to be open about them. There are also lots of resources available, such as books and games, that are great ways to teach children emotional language.

"If your upbringing and experience make this challenging, try to focus on the outcome you want for your child. It may be worth exploring any obstacles with a professional who can help you make sense of your reactions."

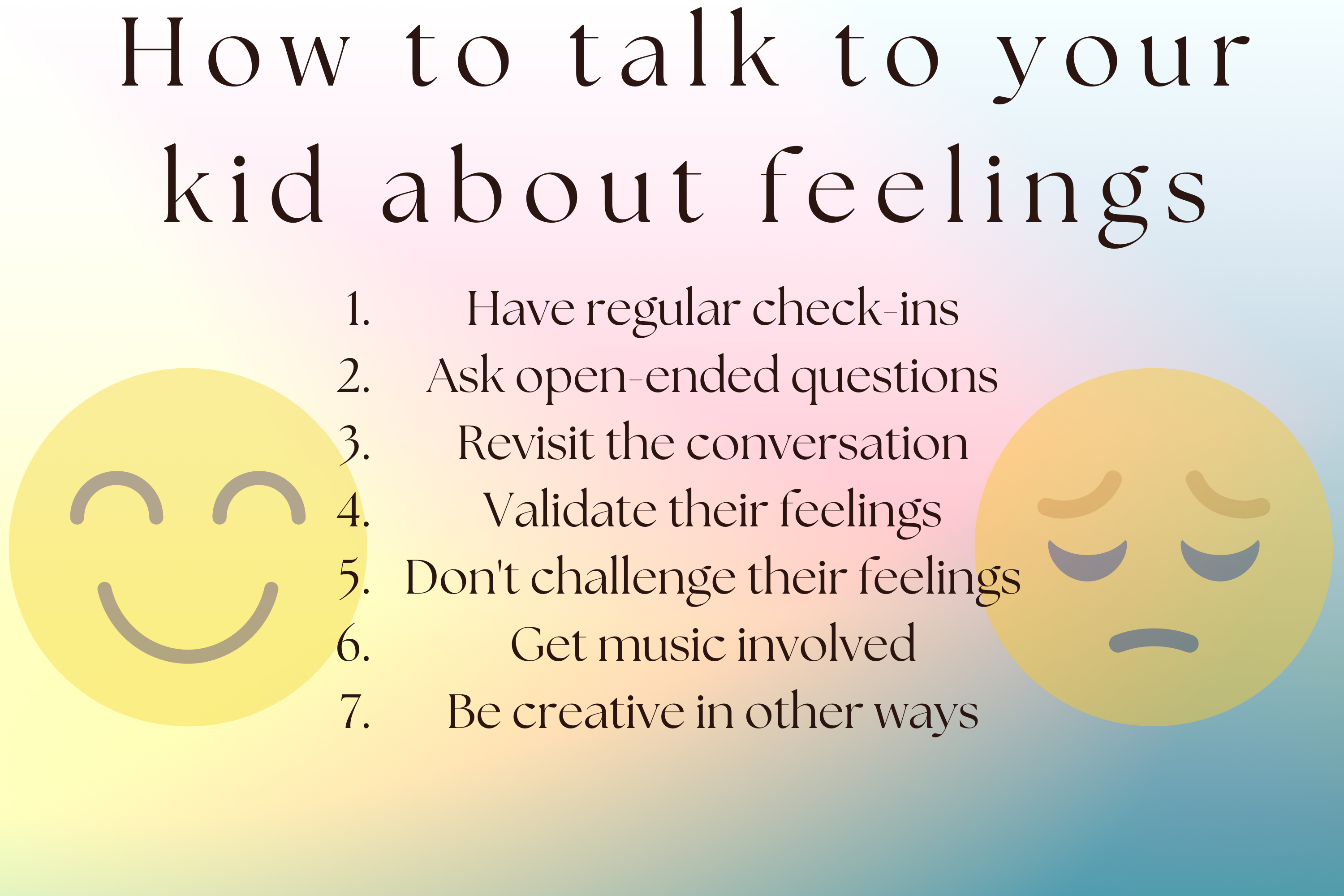

7 expert tips for opening up and continuing conversations

- Have regular check-ins

- Ask open-ended questions

- Revisit the conversation

- Validate their feelings

- Don't challenge their feelings

- Get music involved

- Be creative in other ways

There are many effective ways to encourage your children to talk about their feelings. Child psychologists and therapists have identified several strategies that can help create an open, supportive environment for emotional expression. Let's explore some key methods to get your kids talking about their emotions.

1. Have regular check-ins

"Regular check-ins make it easier to talk about feelings," says Kemi. "If your child is already used to you checking in with their feelings, they are more likely to open up."

Heidi Soholt added that regular check-ins are OK if your child is reluctant to open up, adding, "There are many opportunities to talk to your child about feelings, ranging from simple, everyday chats to discussions about more serious matters like grief or divorce. The important thing to remember is that children need to feel safe to engage."

The research backs this up. A 2022 study into girls aged 10-11 found that providing a safe and supportive environment to children helped them to have fewer mood fluctuations and allowed them to recover more quickly from negative emotions, which aided in opening up conversations.

2. Ask open-ended questions

Open-ended questions needn't even be related to the discussion you're trying to have. They can simply be a mechanism to start up a dialogue. Conversation starters offer your child a whole range of answers, eventually steering the conversation towards where you need it to go. "Open-ended questions can help your child talk about their feelings," says Kemi. "Ensure you allow them some thinking time, and don't rush them for answers."

This can take place around the table at dinner, with each family member sharing something positive from their day. The discussion can then turn to how it made the child feel and whether they want to discuss it further. If discussing with family isn't appropriate, make sure your child feels safe when you approach them. You could open with the question, "What was the most exciting thing that happened today?"

3. Revisit the conversation

This looks a little different from regular check-ins. Check-in is for starting the initial conversation. Once the discussion is underway, your child might bring it to a close before you feel it has ended. That's OK, and you can revisit it again in the future.

Kemi tells us, "It’s okay to revisit the conversation; sometimes children respond better to a little and often approach." Make sure you give them space to have their feelings before you revisit. This could look like just sitting in the same space as them, with no pressure for them to talk. This models mindful behaviour and sets the right tone. Once they look relaxed and ready to re-engage, off you go.

4. Validate their feelings

Children need to feel heard, and that their feelings have meaning. "Give children time to be calm and try to stay with the feeling they’re trying to communicate rather than offering opinions, advice or criticism," says Heidi. "Phrases like 'that seems like a worry' or 'that sounds scary' are neutral and signal that you are validating and listening."

Kemi Omijeh added, "When they open up about their feelings, it’s important to validate them and acknowledge that it’s okay to feel what they feel, even if you don’t agree with it and/or understand it." This could entail simply reminding them that you're always there for them and letting them know it's OK for their thoughts and feelings about something to change and evolve - they don't need to worry if everything feels a little upside down.

Even though we want to help our kids feel positive about everything, accepting that they have negative feelings is crucial. Researchers in a 2021 study found that parents of early years kids who accepted both positive and negative emotions from their children helped them develop emotional expression and better regulate those feelings.

5. Don't challenge their feelings

In the same way children need to know you're on board with what they're trying to tell you, a deeper connection will be held if you don't challenge them. Challenging is likely to result in them becoming closed off. If you're feeling personal difficulty in what they're telling you, this is likely to happen to a lot of parents at some point. Take a breath, and keep your tone neutral and nurturing.

"Be mindful of not questioning or challenging their feelings," warns Kemi. "Children often simply want to feel connected and supported by their adult and sometimes your presence and reassurance is enough." So, no matter how you feel, showing your child they are your absolute priority, will maintain good levels of trust.

6. Get music involved

Music can work wonders for getting children to open up. The earliest songs they learn will have a story to tell. The older they get, the more they understand some songs will convey complex messages. Even if they aren't listening to the words, music can act to calm children down. Listening to their favourite music before a difficult conversation might be the key to it going well.

Mum-of-two, Beate, found a great way to get her child to open up. She told us, "My son has always struggled to talk about his feelings. He loves music and started writing down little song lyrics he'd made up here and there. Then he came to me with an entire page of lyrics to the tune of a popular song that he'd changed to include how he felt. It made me well up because it was really clever and quite a profound way for us to finally get to grips with his real feelings."

Neuroscience and development experts have recognised music as a powerful tool for helping children's emotional development. One 2023 study published by Cambridge University found that music therapy aids children in processing grief and other challenging emotions. Another study in 2019 found that music interventions were particularly useful for children with Autism.

7. Be creative in other ways

You don't have to use music to get your child talking about their feelings. They might know exactly what they want to say, but are simply unable to express themselves verbally, no matter how well you've approached the situation.

"Children may also struggle to articulate feelings, and expecting them to do this may put pressure on them," says Heidi. "If you are sensing your child wants to talk but is struggling, then you could try to offer them another outlet - they could try to draw, paint or make the feeling, or tell it as a story with characters they've made up."

This could take the form of asking your child about their picture, with questions like "Why did you choose that colour?," or "What is this person telling me?" You could read existing books with your child and connect facial expressions of the characters, with a particular emotion. Watch your child during this for any verbal or non-verbal cues that they're ready to move the conversation towards their own feelings.

Examples of conversations

How it sounds: Your child screams "I hate you," and runs away crying.

Why it happens: Heidi Soholt said "If a child has screamed they hate you, mid-tantrum, try not to take it personally. A child will often express rage or anger at those they are closest to and will feel remorse afterwards. When they are calm, try to unpick where the emotion came from. Think about how to convey a message about feelings being okay, and we have choices about what we do with them - this could prompt a useful discussion about consequences.

What you can do about it: Dr Becky has a lot of useful content around this on her Instagram page. As a psychologist, she says "We all deserve to be believed. And when someone doesn't believe our feelings, we all escalate our expression of the feeling in a desperate bid to be taken seriously. Take a deep breath and share simple words like this: 'You're upset, I believe you, tell me more.' You're getting to the core issue, you're not reinforcing bad behaviour. You're getting to the core issue, you're connecting to the actual feeling which is how your child will learn to express themselves more calmly."

How it sounds: Your child comes to you and says "Nobody wants to play with me."

Why it happens: Your child might be tired and had a bad day, leading to disagreements with friends that they see as nobody wanting to play with them. Or, they could genuinely have been in a situation where they were excluded or felt like nobody wanted to be their friend.

What you can do about it: Dr Becky also has advice for this situation. She suggests that this isn't minimised as one off, and kids shouldn't be told things will be better tomorrow. She said "Our feelings are overwhelming because we feel alone in them. When you tell a kid something's not a big deal, or will be better tomorrow, you only make them feel more alone in that feeling, which only makes them feel more overwhelmed. Use these words as a response: 'I'm so glad you're talking to me about this, that sounds hard, I believe you.' What you're doing is removing the aloneness. This actually builds their resilience. Our feelings are looking for support, not solutions."

How it sounds: Your child utters the words "Everyone in my class is better than me at reading."

Why it happens: Although tough to hear, making comparisons can be a natural part of life. While they might not have interpreted their findings correctly, they're learning sensitivity to societies norms and expectations. Comparisons surrounding ability actually helps children grow, and learn to understand their strengths and what they find challenging. While finding out they're weaknesses can be hurtful, there are ways parents can help.

What you can do about it: Dr Becky has further useful insight, advising parents not to tell the child they're wrong and are actually good at the thing they think they aren't - doing this can lower their confidence even more. She told her audience "Say 'I'm glad you're sharing that with me, that feels really tricky. Tell me more, keep going.' When we show our kids we're not scared of their experiences, they learn not to be scared of those same experiences. That's what builds lifelong confidence."

What to do if children say nothing back

There might be times where you simply can't get your child to engage, and that's OK. Kemi Omijeh told us "Try different forms of communication, talking is just one of the ways feelings can be explored. Perhaps your child would prefer to write or draw how they are feeling? It’s possible they might feel pressured and/or uncomfortable in a face-to-face dialogue – so you could use walkie talkies or phones, including recording voicenotes.

You could also make statements and they can give you thumbs up or thumbs down e.g. 'I wonder if you are feeling upset?' If you are really concerned and think your child needs to be talking about their feelings, it’s ok to seek professional help via counselling or play therapy for your child."

Heidi Soholt concluded "If your child doesn’t want to open up about their feelings, then respect this. They may not be ready, and by accepting this they are more likely to communicate in the future. Try to let them know this is okay, that you’re there for them when they want to talk."

How to explain feelings to a kid

"The first and most important piece of learning how to explain feelings to a kid is to acknowledge that you can’t explain things you don’t understand yourself," says Rachel Coler Mulholland, author, counsellor and children's mental health expert. "In other words, step one is expanding your own emotional vocabulary, as well as exploring how those emotions/feelings show up in your body."

Rachel suggests starting off by listing all the feelings you can think of off the top of your head. "The “big 6” are often the easiest – anger, happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, and surprise. If you Google an 'emotion wheel' you will likely be surprised by how many feelings you forgot were possible, and also the minute differences that distinguish related feelings from one another."

She also suggests asking yourself about those feelings and the physical sensations that go along with them. Start with questions like:

- What does your body feel like when you’re angry?

- What about when you’re excited?

- How about scared?

- In love?

- Anxious?

- Do any of them feel similar?

- How do you tell the difference between excited and anxious?

By expanding your own emotional vocabulary and developing a better handle on the somatic sensations related to each feeling, you are better equipped to help kids nourish their own growing emotional intelligence.

For children younger than 6

Rachel suggests keeping the focus on the big six emotions and beginning to tie the emotions to physical feelings. For example, you can say to your child, "I’m feeling angry—that makes me want to stamp my feet!" or "When I'm happy, my heart jumps up and down!" or "My tummy feels bubbly when I'm feeling scared."

"This method of modelling emotional intelligence enables emotions to be understood on both a cognitive level, and also in a way that honours how the emotions interact with our nervous system," explains Rachel. "It also sets the stage for children to begin to develop coping skills for when their emotions become overwhelming – actions like deep breathing, mindful movement, or (guided) progressive muscle relaxation."

For children aged 7 to 11

Children of this age can begin to understand more nuanced emotions as well as how their emotions interact with other people and their experiences, according to Rachel.

"Empathy is much more solid in this age group than their younger counterparts. Children at this age have a firm grasp on the idea that others have different perspectives than them and can begin to better understand the relationship between their nervous system and their thoughts," says Rachel. "Kids this age love concrete examples and facts, so peppering in biology – the nuts and bolts behind why their brain is doing what it's doing – is a fun approach for helping kids this age maintain a mind/body connection."

Rachel has given us some great examples of how you can talk to kids this age about their emotions: "Did you know that being excited and being scared are related? That's why your skin gets all tingly when you're in the haunted house AND when you're getting ready to go on the carnival ride!" Or, "You know how your stomach feels fluttery when you're scared? It's because when your body goes into fight or flight mode, it slows down your digestion and puts most of your energy into being able to breathe and use your muscles if you need to run away from something scary! Helpful if you're staring at a hungry tiger, not super helpful when you're scared about starting at a new school."

For children older than 11 and teens

"This is the age when many kids have the language and cognitive skills to talk about their feelings, but unfortunately, their 'thinking brain' has taken a back seat to those very emotions," says Rachel. "A great place to start is helping them understand that they may find themselves reacting in new and sometimes unexpected ways to situations they have been in before.

So it can be helpful to use phrases such as, "You are going to be growing and changing really quickly over the next few years. As you go through puberty, your brain, hormones, and nervous system might surprise you – for example, you might find yourself getting really angry about something that you could normally shrug off.

Or, "You might pick fights and argue with people because you don't recognise what you're feeling is anxious. You might think you're feeling really tired when you're actually feeling really sad. You know that part of understanding your feelings is connecting what your body feels like to what your mind is thinking, and that can be really hard during adolescence."

Rachel also suggests reassuring your older child or teen that you'll do your best to help them navigate all these fluctuating emotions and help them have the tools and support they need to stay in tune with themselves as best they can.

Why doesn’t my child talk about their feelings?

Kids struggle to talk about their feelings for all sorts of reasons, from a lack of vocabulary to needing time to process those emotions. But you can help by teaching emotion words, modelling expression of emotions, and providing a safe environment for sharing big, and small, feelings.

1. They haven't got the vocabulary

Rachel points out that when kids simply can't use language or skills they haven't learned yet. This is why we need to teach them the words that go with emotions, so they can express themselves clearly. She's suggested a number of ways to help kids build an emotional vocabulary, for example, pointing out emotions in on TV or in stories – “Oh no, she’s crying – she must feel sad.” Or, “Did you see on the last page – they were all jumping up and down because they were so excited.”

"I love to play 'actor' with my kids", says Rachel. I'll put on a silly voice and a very exaggerated facial expression and then name the emotion I’m portraying in my ridiculous scene. 'Oh, I’m DEVASTATED by this news – I cannot BELIEVE you ate the last DONUT!' For my older kids, I will also do the inverse – name an emotion and then act in the complete opposite way a person might expect. It generally gets a pretty solid laugh."

Rachel suggests discussing the nuances of emotions with older kids more, too. "We'll be watching a show, and I'll say something like 'Hold on – that character said they were angry, but I actually think they seemed more frustrated. Their muscles were all tight, and you could see it on their face, but it wasn’t like they wanted to smack that other person – they really just wanted to stop what they were doing and do it themselves because they knew he was going to screw it up!'

2. They haven't practiced

Rachel says it's down to the parents to take the initiative here and start expressing emotions clearly so their kids can exercise their own emotional intelligence. "That way, when they are asked or prompted to share, they know what that looks like!"

3. They've had negative outcomes from sharing

"This is probably the hardest 'reason' to come back from, especially if the negative outcome has come from you," says Rachel. "If a child has been shown previously that expressing their emotions will get them punished, or scolded, or isolated, or ignored, it makes sense that they would avoid expressing their emotions in later situations."

In a situation like this, Rachel says it's on us, as parents, to ensure our kids know they are safe and welcome to express themselves. "If that isn’t true – if you find yourself upset or triggered when your child expresses feelings you didn’t expect – then exploring your own emotional intelligence may be necessary," she says.

4. They're still processing

"Sometimes, kids just need you to stop asking them", says Rachel. "They aren’t ready to express their emotions because they don’t actually know yet what they’re feeling.

"They might need time, or space, or a walk in the park before they can make sense of what their body and brain are doing. In this scenario, I like to remind my kids that I’m not going anywhere, and that I’ll be prepared to hear them when they’re ready."

5. They just don't want to

If you have an older child, a tween or a teen. this will probably sound familiar, and it's completely normal. "Sometimes, we are not the people our kids want to talk to," says Rachel. "They’d rather tell their friends, or their teacher, or their cool aunty. And generally, we need to be ok with that."

However, Rachel warns that you may need to step in if you see signs that your child is struggling. "While I can’t force my child to talk to me, I can offer options for safe places to turn. If they have a support system they can rely on, they feel safe, and they know I'l lbe ready to listen when thye're ready to talk, I will leave them to manage it themselves."

On a more honest and totally relatable note, Rachel outlines why it's so important to ensure our children can open up and talk, so that they can build an 'emotional safety net' for themselves. "Because eventually, I won’t be here. And I hope that they have a chance to practice utilising their emotional safety net before I’m gone."

Where to find more help on talking about feelings

- Ivy's Library is a website for recommendations on books about feelings.

- CAMHS has a page dedicated to signposting parents to websites that help children explore feelings around specific subjects.

- Commonly used in schools, ELSA support has a range of free resources for parents to use at home, to help children find and validate their voice.

- How To Talk To Kids About Anything is a podcast by Dr. Robyn Silverman, where she covers a range of topics, including talking to kids about their feelings.

- Good Inside with Dr. Becky is a podcast from clinical psychologist and mother-of-three, Becky Kennedy. She tackles tough parenting questions and delivers actionable guidance.

- Dr Becky also has over 2million followers on Instagram, sharing easily digestible reels on how to talk to kids about a range of feelings.

- Catherine Hallissey is a child psychologist and mother-of-five. She shares top tips on Instagram relating to communicating with kids about a range of subjects.

- Dr Jazmine is also a psychologist sharing expertise on all things parenting and communicating with children.

Toys to help calm a child before the conversation

Calm your child before difficult conversations with these lava effect sensory toys. With three toys in a pack, each promotes serenity with gently moving lava droplets. Like an hourglass, the lamps can be turned once the lava reaches the bottom, to start the gentle process again.

Talking About Feelings: A book to assist adults in helping children unpack, understand and manage their feelings and emotions, by Jayneen Sanders. The aim of this book is to assist adults in helping children unpack, understand and manage their feelings and emotions in an engaging and interactive way. Great for those looking for a way to 'check in' to see how their child is doing.

The BE Buddy are animal-themed breathing companions and comforting eye pillows. They empower kids to tap into their internal world to manage stress, learn self-care habits, and cultivate a positive connection to themselves and others.

Featured experts

Kemi Omijeh is an experienced BACP registered psychotherapist and clinical supervisor who has worked with children and families for over 14 years. She is also a trainer, and speaker with her specialist subjects being cultural competence, racial identity, racial trauma and antiracist practices in education. Kemi champions inclusive mental health for children and young people, and states that support for young people should include a consideration of the child’s context, culture and identity.

Heidi Soholt is a highly experienced BACP accredited psychotherapist who specialises in helping with children and adults overcome a wide range of issues - including anxiety, low self-esteem and peer difficulties. Heidi has a private therapy practice based in Stirling (Scotland) but also provides remote online support to clients worldwide. She is also a school counsellor and works with children aged 4 to 11.

Rachel Coler Mulholland is a counsellor and children's mental health expert and author of The Birds, the Bees, and the Elephant in the Room - Talking to Your Kids About Sex & Other Sensitive Topics With nearly 1 million followers on TikTok, she is a favourite with parents for her honest, funny, responsible, and much-needed wisdom on talking to kids about bodies, puberty, consent, and sex.

If you're looking for open-ended questions, try this list of conversation starters with your child. We have helpful resources on talking about children's mental health, and some ideas for toys to support their mental health and wellbeing.

Lucy is a mum-of-two, multi-award nominated writer and blogger with six years’ of experience writing about parenting, family life, and TV. Lucy has contributed content to PopSugar and moms.com. In the last three years, she has transformed her passion for streaming countless hours of television into specialising in entertainment writing. There is now nothing she loves more than watching the best shows on television and sharing why you - and your kids - should watch them.

- Joanne LewsleyWriter