How do air traffic controllers make sure flights stay safe? An explainer for kids by The Week Junior

Air traffic controllers make sure thousands of planes stay safe

It’s the summer holidays for schools in the UK and that means many people will be jetting off for holidays. In fact, every day 100,000 planes take off and land around the world, meaning the sky above us can get busy.

Making sure planes are able to reach their destinations safely isn’t just the responsibility of the pilots – there are also lots of people on the ground guiding planes through the skies.

In the UK, 1,700 air traffic controllers are employed by the National Air Traffic Service (NATS). NATS has 15 UK airport control towers – the tall structures you see at airports – and two bases, one in Swanwick, England, and the other at Prestwick, Scotland. Using special technology, these controllers make sure planes are being tracked at all times during their flights. There are air traffic controllers on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

Although air traffic controllers can’t actually see planes most of the time, they know where they are because of radar. Radar is a system that uses radio waves (waves of light that are invisible to the naked eye) to work out where objects are, based on how the waves are reflected off them.

Many air traffic controllers will guide a plane through its flight, giving it permission to take off, providing important information about the weather and wind direction, telling it which airport runway to land on, and much more.

The first air traffic control

The first-ever flight in an aeroplane took place on 17 December 1903. To begin with, planes were mostly used by the military and the postal service. In the 1920s, it became more common for planes to carry paying passengers. As more planes and people took to the air, safety experts began looking at ways to monitor the skies.

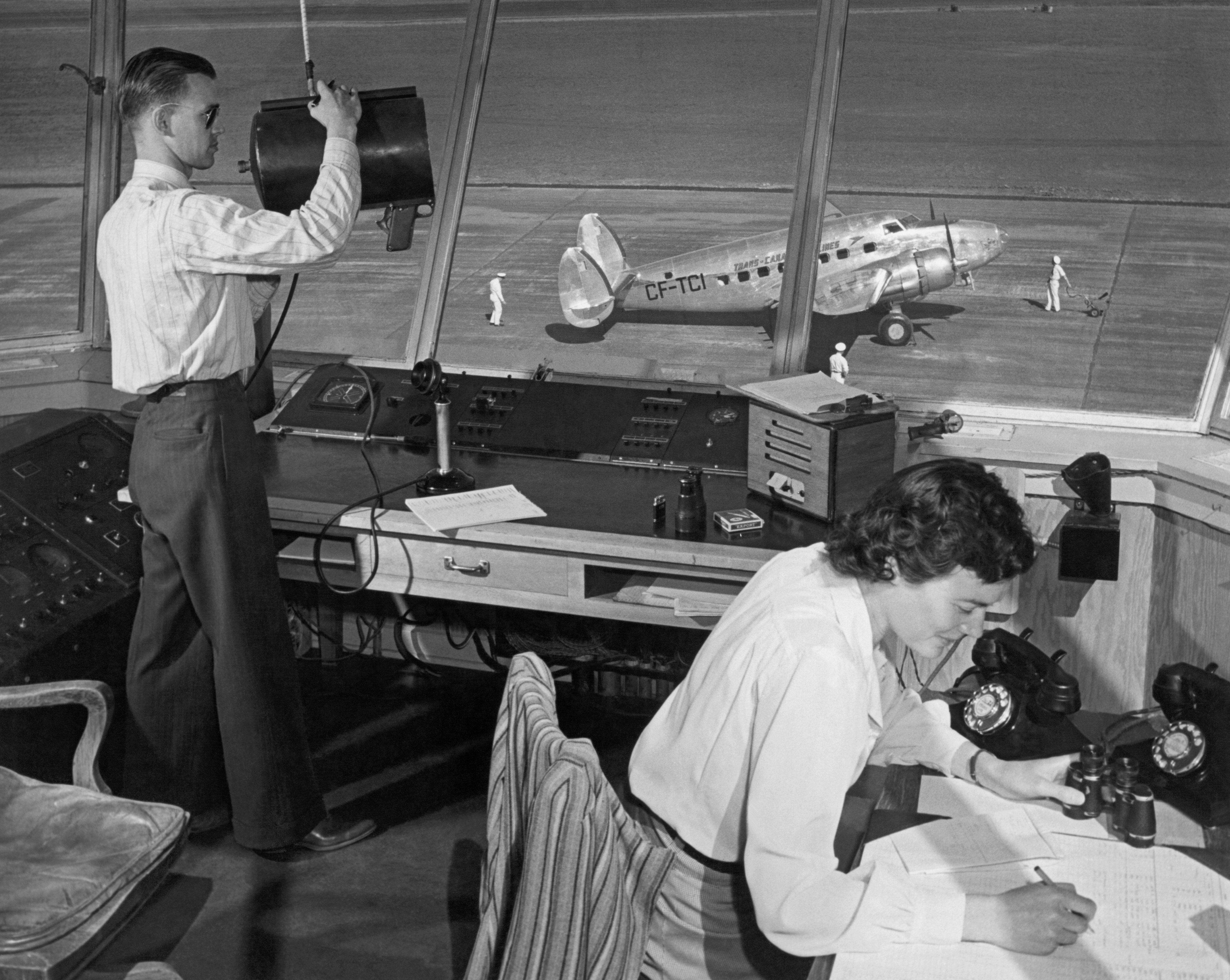

Jimmy Jeffs is thought to have been the world’s first air traffic controller. In 1922, he began work at Croydon Airport, which was on the outskirts of London. The world’s first control tower had been built there. Radio technology helped to keep planes safe thanks to a system called wireless position finding. Pilots could use it to give themselves a route to follow, and air traffic controllers could use it to work out roughly where an aircraft was. A red flag was waved from an observation tower to give the pilots permission to take off.

Air travel today

Despite the arrival of radar in the 1950s, bad weather such as fog can still cause delays today. In thick fog, the trickiest thing for air traffic controllers and pilots is guiding planes to the runways they will take off from. Unable to see what's happening around them, they rely on technology to show where all the planes are.

Back in the mid-20th century, English was chosen as the language of communication in air travel. These days, air traffic controllers use lots of different words to get messages across quickly and clearly. A common example is “roger”, which someone might say after receiving a message to confirm all the information has been received. In addition, each airline has its own special (sometimes funny) callsign – a word that air traffic controllers use to clearly identify certain planes.

GoodtoKnow Newsletter

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

Three interesting callsigns

- Shamrock – Aer Lingus, Irish airline Aer Lingus is known as Shamrock. The shamrock is a type of plant that is used as a symbol of Ireland.

- Viking – Sunclass Airlines, Sunclass, a Danish airline, is known as Viking. This is because the Vikings were a group of people from Scandinavia (an area of northern Europe that includes Denmark).

- Springbok – South African Airlines, South African airlines are called Springbok, after a type of antelope that is the national symbol of the country.

Recent updates

This feature was originally published in May 2024 in The Week Junior, which is also owned by Future Publishing.

Subscribe to The Week Junior

Get your first 6 issues free - saving £21 - when you subscribe to The Week Junior magazine. Continue on subscription and pay just £33.99 every 3 months, saving 25% off the cover price, unless cancelled in the trial period.