The Queen’s annus horribilis: What happened in 1992 and what does the phrase mean?

The meaning behind The Queen's famous phrase

The Queen's 'annus horribilis' of 1992 takes centre stage in The Crown Season Five, but what exactly does the Latin term mean, and what actually happened in the infamous year?

If you're anything like us, you've already binge-watched the entirety of The Crown season five and are now researching every scene of the royal drama's new episodes. From Princess Diana's revenge dress to the Windsor Castle fire and Princess Diana's Panorama interview, there were plenty of shocking royal moments – some fact and some fictional – to dissect after the first viewing of the Netflix series. The fifth series also introduced viewers to a fresh batch of talented newcomers, with acting heavyweights like Imelda Staunton and Dominic West joining The Crown Season Five's cast as the Queen and Prince Charles, respectively. Whilst a famous Australian actress is now playing Diana in The Crown season 5 too - taking over from Emma Corrin's acclaimed stint.

It's no secret that The Crown Season 5 explores the Queen's 'annus horribilis', with Episode 4 even being titled with the Latin term. Her Majesty uttered the phrase herself in November 1992 during a public speech, in reference to the string of misfortunes she'd endured over the last eleven months. Here's everything you need to know about what exactly 'annus horribilis' means, and why Her Majesty used it to describe her painful year.

What does annus horribilis mean?

'Annus horribilis' is Latin for a disastrous or horrible year, with its first known usage dating back to 1890. It became much more famous though following Queen Elizabeth's speech in 1992.

Its earliest citation in print is from a report in The Guardian, March 1985: "Unlike the earlier Kostelec stories, however, The Engineer of Human Souls was written in exile in Toronto, where he was driven by the annus mirabilis, annus horribilis of 1968."

It was again used in the Sunday Times in 1988 and the Financial Times in 1990, before skyrocketing into mainstream discourse after the Queen first used it in 1992.

On the flip side, "annus mirabilis", the Latin for 'wonderful year', has been around for centuries. It's understood it was first used in John Dryden's 1667 poem, 'Annus Mirabilis', which detailed the Great Fire of London.

GoodtoKnow Newsletter

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

Why was 1992 called annus horribilis?

The Queen called 1992 an 'annus horribilis' as it was a disastrous year for the Royal Family. Her Majesty endured a litany of hardships over the 12 months, including the collapse of three royal marriages and a devastating fire at Windsor Castle.

The British monarchy's reputation during this period was also in serious jeopardy, as public concerns for its lavish spending and relevance in a modern world grew in the face of rising social inequality.

The Queen first used the term 'annus horribilis' on November 24, 1992, during a speech at London Guildhall.

"1992 is not a year on which I shall look back with undiluted pleasure. In the words of one of my more sympathetic correspondents, it has turned out to be an annus horribilis," she said, before adding, "I suspect that I am not alone in thinking it so."

Queen delivers her famous 'annus horribilis' speech in 1992

What happened in the Queen's annus horribilis?

The Queen's annus horribilis of 1992 was marked by a series of unfortunate events for the monarch, culminating with a devastating fire at her beloved Windsor Castle in Berkshire.

Caused by a faulty spotlight, the blaze broke out on November 20 and took emergency services over 15 hours to extinguish. Over 100 rooms were destroyed by the fire, including Queen Victoria's chapel and St George’s Hall. The damages cost a whopping £36.5 million to repair.

The fire at Windsor Castle had been preceded by a year of strained family relations for the Queen, most of which related to her grown children's tumultuous romantic lives. At the beginning of 1992, UK tabloids published photos of her daughter-in-law, the Duchess of York, that linked her to Texas millionaire Steve Wyatt. That March, Sarah Ferguson filed for divorce from Prince Andrew.

In April, Princess Anne divorced from her husband, Mark Phillips, after 19 years of marriage. The couple had been separated since 1989, however, having reportedly both engaged in extramarital romances. In December 1992, Anne married Navy officer, Timothy Laurence, after years of close friendship.

The most famous royal split to occur in the Queen's annus horribilis, or perhaps ever, was the divorce of Prince Charles and Princess Diana. The couple had endured problems in their marriage ever since their 1981 royal wedding, with the prince's affair with Ms. Camilla Parker Bowles dooming the union from the start.

Princess Diana was reportedly also unfaithful, dating a number of other men – including army captain James Hewitt – during the marriage. They separated in 1992 after details of their respective affairs started to make headlines news and the truth of their unhappy marriage became impossible for the Royal Family to ignore. Their divorce was finalized in 1996, one year before Princess Diana's tragic death.

The Queen’s Annus Horribilis speech in full

On 24 November 1992, the Queen delivered the following speech at Guildhall in London, to mark the 40th anniversary of her ascension:

My Lord Mayor,

Could I say, first, how delighted I am that the Lady Mayoress is here today.

This great hall has provided me with some of the most memorable events of my life. The hospitality of the City of London is famous around the world, but nowhere is it more appreciated than among the members of my family. I am deeply grateful that you, my Lord Mayor, and the Corporation, have seen fit to mark the fortieth anniversary of my Accession with this splendid lunch, and by giving me a picture which I will greatly cherish.

Thank you also for inviting representatives of so many organisations with which I and my family have special connections, in some cases stretching back over several generations. To use an expression more common north of the Border, this is a real 'gathering of the clans'.

1992 is not a year on which I shall look back with undiluted pleasure. In the words of one of my more sympathetic correspondents, it has turned out to be an 'Annus Horribilis'. I suspect that I am not alone in thinking it so. Indeed, I suspect that there are very few people or institutions unaffected by these last months of worldwide turmoil and uncertainty. This generosity and whole-hearted kindness of the Corporation of the City to Prince Philip and me would be welcome at any time, but at this particular moment, in the aftermath of Friday's tragic fire at Windsor, it is especially so.

And, after this last weekend, we appreciate all the more what has been set before us today. Years of experience, however, have made us a bit more canny than the lady, less well versed than us in the splendours of City hospitality, who, when she was offered a balloon glass for her brandy, asked for 'only half a glass, please'.

It is possible to have too much of a good thing. A well-meaning Bishop was obviously doing his best when he told Queen Victoria, "Ma'am, we cannot pray too often, nor too fervently, for the Royal Family". The Queen's reply was: "Too fervently, no; too often, yes". I, like Queen Victoria, have always been a believer in that old maxim "moderation in all things".

I sometimes wonder how future generations will judge the events of this tumultuous year. I dare say that history will take a slightly more moderate view than that of some contemporary commentators. Distance is well-known to lend enchantment, even to the less attractive views. After all, it has the inestimable advantage of hindsight.

But it can also lend an extra dimension to judgement, giving it a leavening of moderation and compassion - even of wisdom - that is sometimes lacking in the reactions of those whose task it is in life to offer instant opinions on all things great and small.

No section of the community has all the virtues, neither does any have all the vices. I am quite sure that most people try to do their jobs as best they can, even if the result is not always entirely successful. He who has never failed to reach perfection has a right to be the harshest critic.

There can be no doubt, of course, that criticism is good for people and institutions that are part of public life. No institution - City, Monarchy, whatever - should expect to be free from the scrutiny of those who give it their loyalty and support, not to mention those who don't.

But we are all part of the same fabric of our national society and that scrutiny, by one part of another, can be just as effective if it is made with a touch of gentleness, good humour and understanding.

This sort of questioning can also act, and it should do so, as an effective engine for change. The City is a good example of the way the process of change can be incorporated into the stability and continuity of a great institution. I particularly admire, my Lord Mayor, the way in which the City has adapted so nimbly to what the Prayer Book calls "The changes and chances of this mortal life".

You have set an example of how it is possible to remain effective and dynamic without losing those indefinable qualities, style and character. We only have to look around this great hall to see the truth of that.

Forty years is quite a long time. I am glad to have had the chance to witness, and to take part in, many dramatic changes in life in this country. But I am glad to say that the magnificent standard of hospitality given on so many occasions to the Sovereign by the Lord Mayor of London has not changed at all. It is an outward symbol of one other unchanging factor which I value above all - the loyalty given to me and to my family by so many people in this country, and the Commonwealth, throughout my reign.

You, my Lord Mayor, and all those whose prayers - fervent, I hope, but not too frequent - have sustained me through all these years, are friends indeed. Prince Philip and I give you all, wherever you may be, our most humble thanks.

And now I ask you to rise and drink the health of the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London.

*Source: Royal Family website

Related Netflix Features:

- The Crown Cast: Season 1 to season 5 actor guide and where you've seen them before

- Where was The Crown filmed? Season 1 - 5 filming locations

- The Crown season 5 trailer

- Prince Philip and Penny Knatchbull: Who is the Prince’s friend, and who plays her in The Crown season 5?

- How did Dodi meet Diana? Their relationship explained ahead of The Crown Season 5

- Where is Martin Bashir now - and why was the Princess Diana interview so controversial?

- How did Princess Diana know Imran Khan, and what happened to him?

- Reliving memories in Netflix’s new season of The Crown will be “incredibly hard" for Prince Harry and Prince William, claims royal expert

- Has Camilla, Queen Consort got children and who are her grandchildren?

Video of the Week

Emma is a Lifestyle News Writer for Goodto. Hailing from the lovely city of Dublin, she mainly covers the Royal Family and the entertainment world, as well as the occasional health and wellness feature. Always up for a good conversation, she has a passion for interviewing everyone from A-list celebrities to the local GP - or just about anyone who will chat to her, really.

-

Balamory is back after two decades - why we can’t wait for the reboot of the iconic BBC series

Balamory is back after two decades - why we can’t wait for the reboot of the iconic BBC seriesWhat's the story in Balamory? Now you can find out, as the BBC announces the return of the beloved children's series nearly 20 years after the final episode aired.

By Lucy Wigley

-

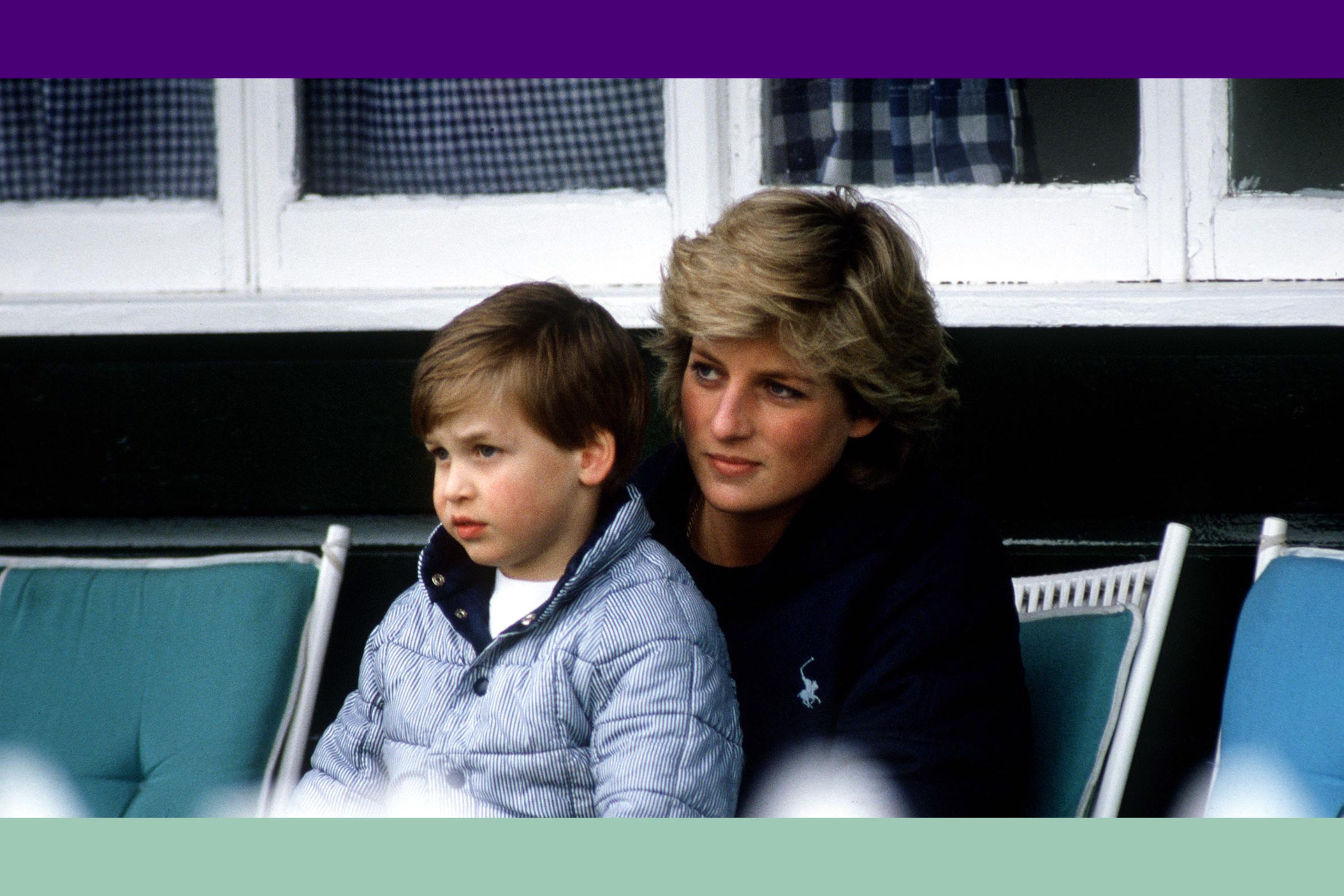

Princess Diana could be about to spark Prince Harry and Prince William’s reconciliation, with adorable 'saved' childhood memory

Princess Diana could be about to spark Prince Harry and Prince William’s reconciliation, with adorable 'saved' childhood memoryThe two princes shared an incredibly close bond growing up

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse

-

Kate Middleton laid out ‘bold’ family priorities in candid conversation with Queen Elizabeth II, new book reveals

Kate Middleton laid out ‘bold’ family priorities in candid conversation with Queen Elizabeth II, new book revealsThe Princess of Wales has always been clear about she plans to raise her three children

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse

-

Princess Charlotte’s name fulfilled Prince William’s final promise to his mum Princess Diana, royal expert reveals

Princess Charlotte’s name fulfilled Prince William’s final promise to his mum Princess Diana, royal expert revealsThe Prince and Princess of Wales's daughter has a very sentimental name

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse

-

Princess Diana’s former royal butler reveals why there’s pressure on Prince William to ‘finish her legacy’

Princess Diana’s former royal butler reveals why there’s pressure on Prince William to ‘finish her legacy’The late Princess's work had 'only just begun' when she died and Prince William is keen to carry it on

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse

-

Royal expert reveals Prince William’s ‘greatest tribute to his mother’ Princess Diana as he celebrates her 63rd birthday

Royal expert reveals Prince William’s ‘greatest tribute to his mother’ Princess Diana as he celebrates her 63rd birthday"I wanted her to be proud of the person I'd become"

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse

-

Queen Elizabeth's heartwarming approach to motherhood revealed in rare letter - and the note includes a hilarious joke about young King Charles III

Queen Elizabeth's heartwarming approach to motherhood revealed in rare letter - and the note includes a hilarious joke about young King Charles IIIA personal letter penned by the late monarch in 1950 has given sweet insight into her life as a young mother

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse

-

Prince William is keeping Prince George, Charlotte and Louis’ feet on the ground with an important project inspired by Princess Diana

Prince William is keeping Prince George, Charlotte and Louis’ feet on the ground with an important project inspired by Princess DianaThe Prince of Wales is keen to carry on the work started by his late mother, a royal expert has revealed

By Charlie Elizabeth Culverhouse